I used the STI pattern in my little Rails app today, the second time I used this in a Rails app and I really like the pattern. The first time it was a lot harder since I was refactoring some existing tables into the new STI table and the app already had production data that had to be moved to the new table carefully. The Rails API documentation on the STI pattern is pretty short and worth reading if you develop with Rails and haven’t already.

It just involves having a table with a type column, and the values for that column will be the names of the child classes derived from a model class corresponding to that table with the Active Record O/RM (a model Ingredient corresponds to the ingredients table). In my case today, the table was ingredients for the parent class Ingredient with 4 child classes. In the current schema.rb file here is the table:

create_table "ingredients", force: :cascade do |t|

t.string "name", null: false

t.integer "category_id"

t.datetime "created_at", null: false

t.datetime "updated_at", null: false

t.string "type", null: false

t.boolean "available", default: true

t.integer "count", default: 0

t.string "volume_unit"

t.float "volume_amount", default: 0.0

t.string "weight_unit"

t.float "weight_amount", default: 0.0

endThe type column determines what class is used to instantiate the object corresponding to the database record. Those derived classes have attributes specific to them (for example here, volume_amount is for VolumeIngredient) but all the attributes are stored in the same table. Here are the models derived from Ingredient:

class CountIngredient < Ingredient; endclass ExcessIngredient < Ingredient; endclass VolumeIngredient < Ingredient

def self.volume_units

["ml", "cups"]

end

endclass WeightIngredient < Ingredient

def self.weight_units

["gram", "lb"]

end

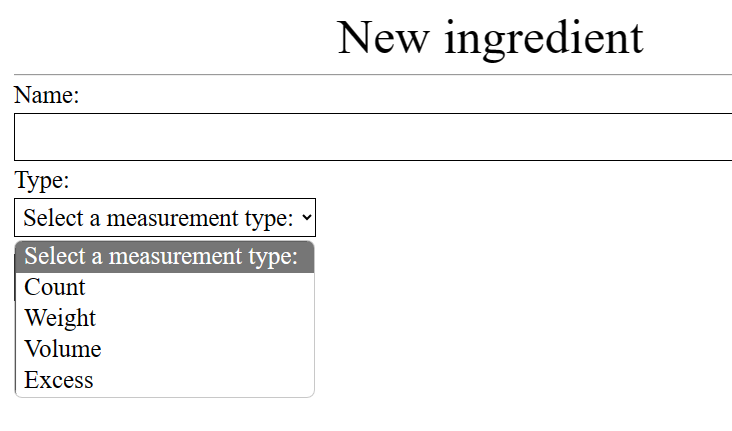

endWith my design, ingredients are created with a name and a type:

The data posted from that select form element is really VolumeIngredient if the user selects Volume there.

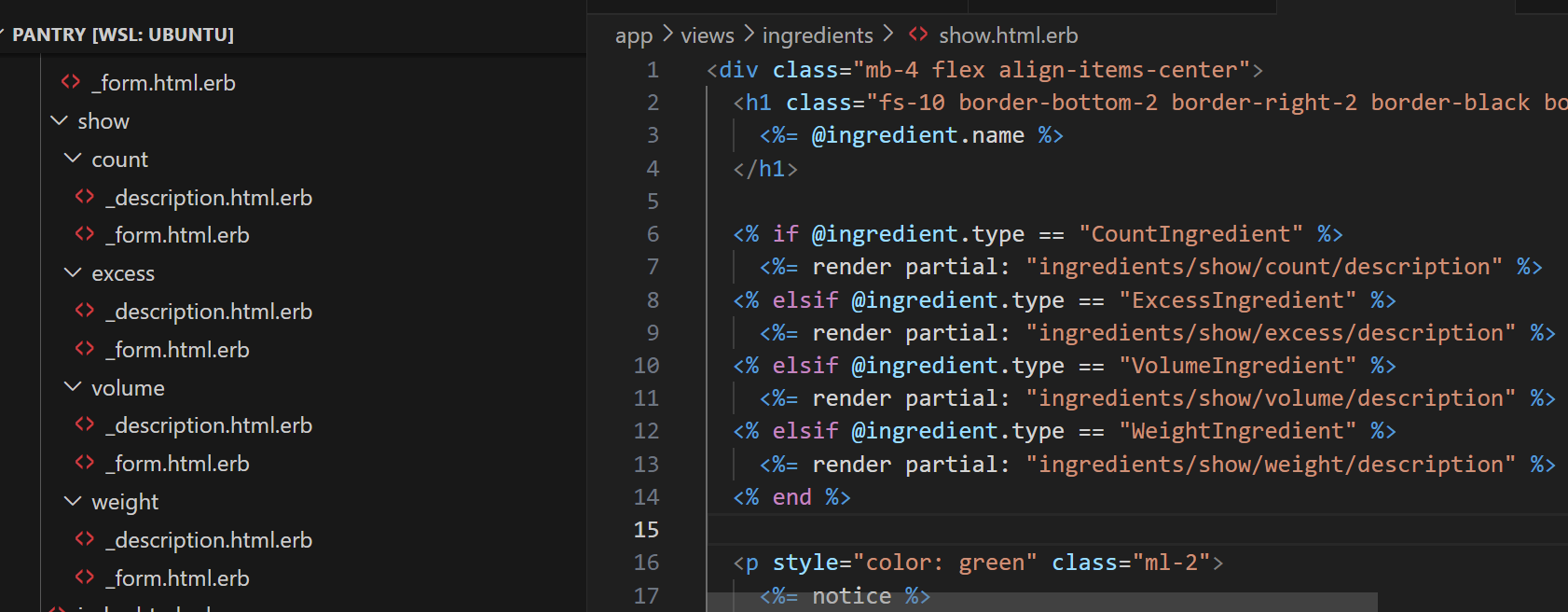

I decided to use the ingredients#show in the following way:

<div class="mb-4 flex align-items-center">

<h1 class="fs-10 border-bottom-2 border-right-2 border-black border-style-groove mr-4 pr-2 pb-2">

<%= @ingredient.name %>

</h1>

<% if @ingredient.type == "CountIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/count/description" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "ExcessIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/excess/description" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "VolumeIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/volume/description" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "WeightIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/weight/description" %>

<% end %>

<p style="color: green" class="ml-2">

<%= notice %>

</p>

</div>

<div class="p-2 border-around-1 border-style-solid">

<% if @ingredient.type == "CountIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/count/form" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "ExcessIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/excess/form" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "VolumeIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/volume/form" %>

<% elsif @ingredient.type == "WeightIngredient" %>

<%= render partial: "ingredients/show/weight/form" %>

<% end %>

</div>

<div class="mt-2 flex justify-around">

<%= link_to "Back to ingredients", ingredients_path %>

<%= button_to "Destroy this ingredient", ingredient_path(@ingredient), method: :delete %>

</div>I like organizing view code of partials into subdirectories named after the action if they are only used in one in general.

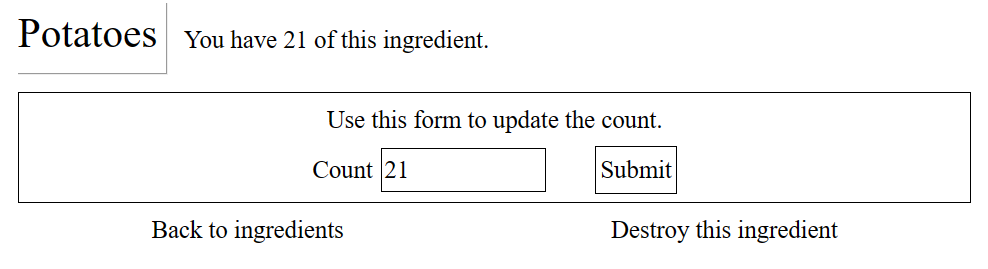

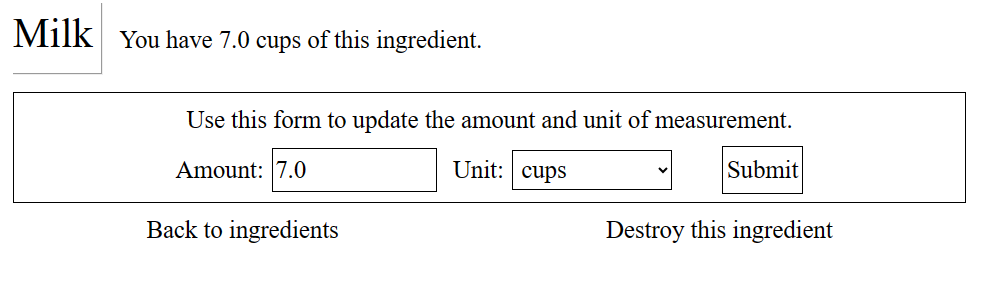

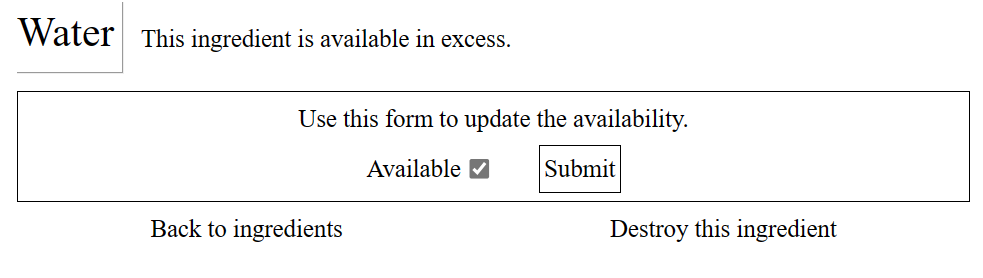

But the main thing is the template uses the partials in a very structured way that reflects the STI. The ingredients#show action responds to a GET request to ingredient_path(@ingredient) for any ingredient type. Simply checking the type of the ingredient in the template and rendering the version of the partial for that ingredient type allows for this sort of thing:

The one for type “WeightIngredient” is pretty similar to the volume one. Here’s an example of the _form.html.erb (in the weight folder):

<%= form_with model: @ingredient, url: weight_ingredient_path(@ingredient) do |form| %>

<p class="text-align-center">

Use this form to update the amount and unit of measurement.

</p>

<div class="flex justify-center mt-2">

<div class="flex justify-center mr-12">

<div class="flex align-items-center mr-4">

<%= form.label :weight_amount, "Amount:" %>

<%= form.number_field :weight_amount,

step: "any",

min: 0,

class: "ml-2",

required: true %>

</div>

<div class="flex align-items-center">

<%= form.label :weight_unit, "Unit:" %>

<%= select_tag "weight_ingredient[weight_unit]",

options_for_select(WeightIngredient.weight_units, @ingredient.weight_unit),

prompt: "Select a unit:",

title: "Select a unit:",

required: true,

class: "ml-2" %>

</div>

</div>

<div>

<%= form.submit "Submit" %>

</div>

</div>

<% end %>It sends the request to an endpoint that is specific to the ingredient type and there is a controller for each. Here are the routes:

Rails.application.routes.draw do

...

resources :ingredients

patch "/excess_ingredients/:id", to: "excess_ingredients#update", as: "excess_ingredient"

patch "/count_ingredients/:id", to: "count_ingredients#update", as: "count_ingredient"

patch "/volume_ingredients/:id", to: "volume_ingredients#update", as: "volume_ingredient"

patch "/weight_ingredients/:id", to: "weight_ingredients#update", as: "weight_ingredient"

...

endAnd one of the controllers:

# frozen_string_literal: true

class WeightIngredientsController < ApplicationController

before_action :set_ingredient

def update

if @ingredient.update(ingredient_params)

redirect_to ingredient_url(@ingredient), notice: "Ingredient was successfully updated."

else

render :show, status: :unprocessable_entity

end

end

private

def set_ingredient

@ingredient = WeightIngredient.find(params[:id])

end

def ingredient_params

params.require(:weight_ingredient).permit(:weight_amount, :weight_unit)

end

endSummary

Rails makes the STI pattern about as easy as it could be to implement (just have a table with a type column, child classes of the model of that table, and put the names of those child classes in that type column). Then a simple implementation to reflect that in the view layer is to just implement the same partial once for each type wherever the UI in a template should vary with the type. I always find code with a structure that has a clear relationship to the data’s structure to be elegant and with STI there are many ways that could manifest itself including the simple design shown here.